Designing for two

Modern cloud work is hard. I’ve seen this firsthand from both sides — developers trying to ship features, and operators trying to keep systems coherent as they scale.

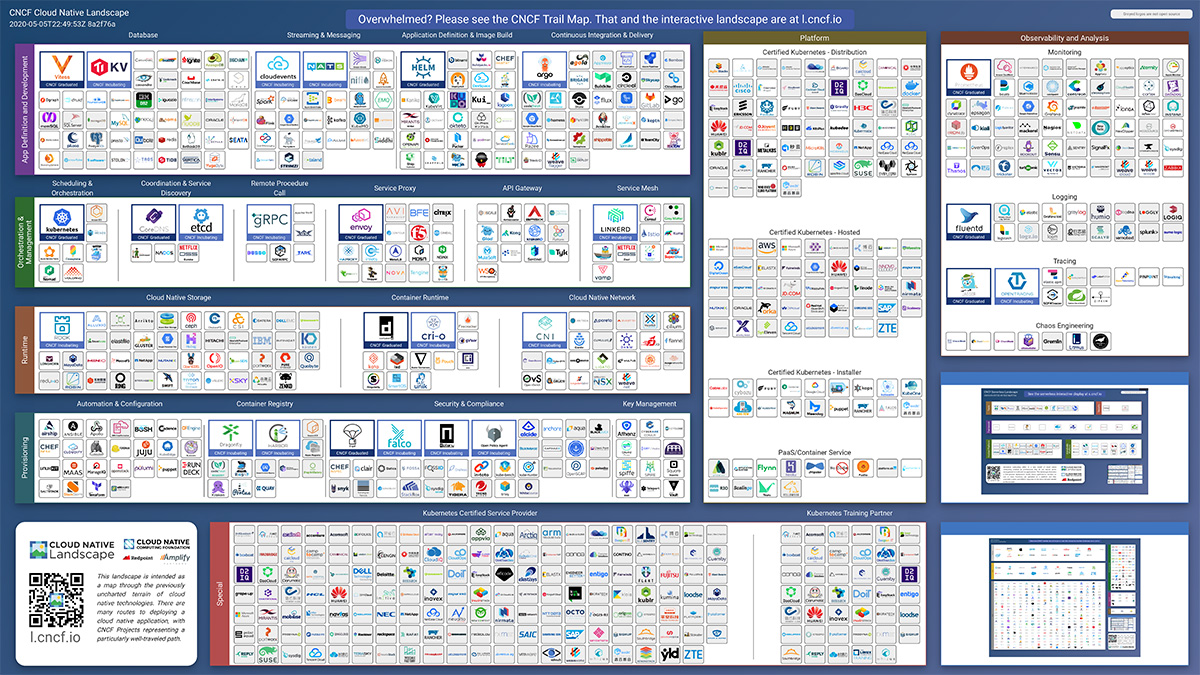

In response, the industry has produced an enormous body of tooling to manage complexity. Entire subindustries now exist around scheduling, isolation, observability, and deployment. We have systems like Kubernetes and HashiCorp Nomad for scheduling, containers and microVMs for isolation, and observability stacks built on OpenTelemetry, Prometheus, and Grafana.

These components are mature, powerful, and widely accessible. The internet has had time to grow up, and it shows. I’m genuinely proud of what this industry has built. The CNCF landscape is an incredible artifact of collective engineering effort.

But that pride comes with a quieter anxiety. The same ecosystem that demonstrates our success also reflects the cognitive and organizational burden placed on teams. Even the CNCF seems to acknowledge this — “Overwhelmed? Please see the CNCF Trail Map.”

My read is that much of this tension comes from how we coordinate across such a vast surface area. Many of the tools we rely on are deliberately general-purpose: maximally expressive, broadly applicable, and flexible enough to model almost anything. In practice, however, real teams are heterogeneous. They consist of people with different intuitions, tolerances for abstraction, and relationships to code.

Some engineers thrive inside a Turing-complete configuration language. Others prefer constrained, declarative systems. Some are comfortable writing shell glue; others actively avoid it. Generalist tools flatten these differences, often pushing complexity into shadow work — ad-hoc scripts, translation layers, and tests written to recover clarity the tooling itself cannot express.

This project grew out of an attempt to address that tension more directly.

Coordination as a design problem

I approached these challenges by studying how existing tools resolve coordination in practice, and by experimenting with alternative ways of composing those tools to make their tradeoffs more legible.

My project is motivated by a different core principle than much of the existing tooling: less power, more understanding — where power is the ability to express arbitrary behavior, and understanding is the ability to reason locally about outcomes.

One way I’ve found it helpful to visualize this tradeoff space is:

Understanding here means being able to predict, with confidence, how the system will behave when acted upon.

A legible system is one where the truth about behavior lives in artifacts you can read, rather than being buried inside program execution.

The tension here is not technical capability, but how easily different people can share a correct mental model of the system.

I first developed these intuitions in application systems, where state and behavior were tightly coupled and often implicit. In those environments, ad-hoc abstractions and localized logic made global reasoning difficult, even when individual components were well-designed. Systems that instead made dataflow explicit — modeling dependencies as directed graphs and centralizing state transitions — dramatically improved correctness and debuggability. The same tradeoffs reappear at infrastructure scale, where hidden execution paths and implicit authority have even larger consequences.

The system I built exposes distinct interfaces for different audiences. These are designed to reinforce rather than obscure one another, while keeping both initial provisioning and ongoing operational change within a single, continuously reconciled control plane.

Developers interact with it primarily through executable tests that assert deployment invariants. Operators work through schema-driven configuration that constrains and validates system shape. Hermetic build tooling ties these layers together without collapsing them into a single abstraction.

This project is a design experiment. It is not battle-tested at scale and should not be used in production. The goal is not replacement, but exploration.

There is also absolutely a time and a place for Terraform, YAML, and bash glue. Most organizations should coordinate around them. They have too much momentum to ignore, and they work extremely well for small to medium-sized teams.

But if you’re in a position to experiment, it’s worth paying attention to newer tooling and methodologies that have emerged from larger organizations over the past few years. To make that concrete, it helps to look at how existing tools resolve this problem today.

Preexisting tooling

Terraform

Terraform has, for good reason, become the de facto coordination layer for cloud infrastructure. It was the primary catalyst for the widespread adoption of Infrastructure as Code, and it remains the most widely deployed tool discussed here.

Terraform is pleasant to read. It borrows the most ergonomic parts of JSON, offers a simple static type system with solid editor support, and avoids unnecessary complexity. Its most important contribution, however, is its state model.

In real-world deployments involving multiple teams, the world changes underneath you. Machines are reassigned. IP addresses expire. Ownership shifts. Configuration alone is not enough to describe reality.

Terraform addresses this with a deceptively effective loop: refresh, plan, apply. Desired configuration is reconciled against stored state and the provider’s current view of the world. The resulting execution plan describes how to restore consistency, and the applied outcome becomes the new state.

This model enables drift tolerance, shared ownership, and long-lived systems. It also enforces a clear tradeoff: coordination is centralized.

The cost is operational. At any given moment, only one actor can safely perform the refresh–plan–apply cycle. Locks and workflows mitigate this, but do not remove the underlying constraint. For small teams this is often acceptable; for larger or more parallel organizations, the apply cycle becomes a scarce resource that shapes how work is planned and delegated.

Terraform succeeds by becoming the system of record for reality — and that success inevitably shapes the organizations that adopt it.

Pulumi

Terraform’s push-based reconciliation model proved so effective that most subsequent tools preserved it. Pulumi is best understood as one such iteration.

Rather than rejecting Terraform’s model, Pulumi reimplements it using general-purpose programming languages, shifting expressiveness and abstraction into user programs while keeping centralized state as the coordination primitive.

Architecturally, Pulumi consists of a Go-based engine and a set of language hosts that communicate with it over a defined RPC protocol. User programs run as normal processes in languages like TypeScript, Python, Go, or C#, but instead of mutating infrastructure directly, they register intent with the engine. Dependency tracking, diffing, ordering, and state persistence remain centralized.

This design is pragmatic and elegant. It allows Pulumi to support many languages without duplicating its core logic, and it lets organizations reuse their existing ecosystems wholesale. For application-centric teams, this is a powerful wedge.

Pulumi’s defining feature is that infrastructure intent can be expressed using the full abstraction power of the host language. Loops, conditionals, helper functions, and classes are all available, and infrastructure definitions can live directly alongside application code.

This is also where the core tradeoff appears.

By allowing intent to be expressed as the result of general-purpose program execution, Pulumi moves a significant amount of authority out of the tool and into user code. The shape of the desired system no longer exists as a static artifact; it is produced indirectly, by running a program.

In environments where infrastructure intent is primarily expressed through general-purpose code, authority tends to accumulate implicitly: in helper libraries, custom tooling, sidecar processes, and extension points that are difficult to inspect in isolation. Over time, onboarding becomes an exercise in reconstructing execution paths rather than reasoning about declared state. Even when individual components are well-designed, the system as a whole fragments into behavior that is correct but no longer legible.

This raises the bar for control planes, automation, and auditability. Systems that sit above infrastructure definition depend on stable, statically analyzable interfaces. Operators and administrators need to inspect intent without replaying arbitrary execution.

Pulumi does not make this impossible, but it enforces discipline culturally rather than structurally. In environments where application teams own infrastructure end-to-end, that tradeoff can be reasonable. My own interests lie elsewhere: in systems where control-plane boundaries are explicit, interfaces are static, and intent remains inspectable without executing arbitrary programs.

CDK8s

At first glance, CDK8s appears similar to Pulumi. Both allow infrastructure to be authored in general-purpose languages and primarily target application developers.

The difference lies in scope and execution.

CDK8s is not a general-purpose cloud framework. It does not manage state, perform reconciliation, or call provider APIs. Instead, it focuses narrowly on Kubernetes, allowing users to define resources using object-oriented abstractions and then synthesize those definitions into static YAML. Application and reconciliation are left explicitly to downstream systems.

In that sense, CDK8s functions more like a compilation target than a control plane.

This was initially very attractive. CDK8s is intentionally constrained, produces artifacts that are legible to operators, and integrates cleanly with GitOps workflows. It eliminates a class of configuration errors without obscuring the underlying manifests.

Over time, however, two issues became difficult to ignore.

First, the object-oriented abstractions sit at a noticeable semantic distance from the YAML they generate. Writing and reviewing configurations required frequent context switching between representations of the same intent. As configurations grew — especially when targeting systems like Crossplane — that indirection made local reasoning harder rather than easier.

Second, CDK8s is explicitly an application-level abstraction over Kubernetes. Its strengths lie in ergonomic builders for well-known resources, not in serving as a substrate for control-plane-level composition across many CRDs.

Those edges clarified what I was actually looking for: a system that preserves static, inspectable artifacts, but with a simpler and more direct evaluation model.

YAML and bash

At the far end of this spectrum sit YAML and shell scripts. Despite their limitations, they remain ubiquitous for a reason: they are flexible, transparent, and require very little machinery.

The cost is that execution and reconciliation are pushed almost entirely onto the user. There is no shared state, no formal notion of intent, and no control plane mediating change. Invariants live in documentation and convention rather than in the system itself.

For small teams, this tradeoff is often acceptable. As a general coordination model, however, YAML and bash offer few affordances for auditability, automation, or shared ownership. They expose execution without structure — powerful precisely because they make no promises.

The system I built

After evaluating Terraform, Pulumi, CDK8s, and raw YAML, I arrived at a conclusion that surprised me: these tools do not strain because they lack power, but because they collapse too many concerns into a single interface.

Infrastructure systems serve multiple audiences at once. Application developers want leverage. Operators want legibility and predictability. Platform and security teams want auditability and enforceable constraints. Most tools optimize for one of these roles and ask the rest to adapt.

This project explores a different approach: separating power from authority, and binding them back together through static, inspectable interfaces.

https://github.com/becker63/static-control-plane/

A constrained control plane

At the center of the system is a Kubernetes-based control plane built on Crossplane. Unlike Terraform’s push-based apply loop, Crossplane exposes state continuously through Kubernetes objects. Desired and observed state live in the same substrate, making the system observable by default and naturally compatible with GitOps workflows.

This continuous reconciliation model also collapses the traditional distinction between “Day 1” provisioning and “Day 2” operations. Initial creation, drift remediation, scaling, replacement, and upgrade are all expressed through the same declarative topology and observed through the same control plane. Rather than handing systems off from a provisioning phase to an operational phase, Crossplane treats infrastructure as a long-lived object whose lifecycle remains visible, auditable, and correctable over time.

Crossplane’s native composition mechanisms are intentionally conservative. Rather than bypassing that constraint, I leaned into it.

All composition logic in this system is written using KCL, a small, non-Turing-complete language with a deliberately narrow execution model. KCL always evaluates to either valid Kubernetes manifests or a hard error. There is no synthesis step, no intermediate representation, and no opaque compilation target. Evaluation happens directly inside the control plane via a FluxCD controller that executes KCL as part of reconciliation.

This distinction matters.

KCL is not used here as a code generation language. It is used as a structured, executable configuration format whose syntax and semantics closely mirror JSON and YAML. Given the same inputs, it deterministically emits the same resources — or fails loudly.

These KCL functions act as pure transformations over observed state. They cannot perform I/O, spawn processes, or introduce side effects. They exist entirely within the reconciliation loop and can only emit declarative resources.

In practice, this means the control plane evaluates configuration as data transformations, not as programs.

The result is a control plane that is:

-

statically analyzable,

-

auditable by non-programmers,

-

and safe to automate aggressively.

Operators can read the emitted YAML. Reviewers can diff it. CI systems can validate it. There is no hidden execution model.

Code where it belongs

I did not want to give up the benefits of code entirely. Real systems require conditional logic, schema alignment, and cross-resource wiring that is brittle to express in raw YAML alone.

To address this, the system introduces code only at the edges, where it can be reasoned about locally and executed outside the control plane.

Schemas are generated from upstream sources — CRDs, Go structs, and JSON Schema — using hermetic build rules. These schemas are imported into KCL, providing strong typing and editor support without turning configuration into a general-purpose program.

Executable tests assert invariants about system topology rather than imperatively provisioning infrastructure. Build tooling (Buck2 + Nix) ensures that schema generation and evaluation are reproducible and independent of developer machines.

Crucially, none of this code runs as part of reconciliation.

In other words:

-

Code defines structure, not outcomes.

-

Behavior emerges through reconciliation, not scripts.

-

Authority flows through schemas, not conventions.

These ideas become concrete at the boundaries of the system, where static intent meets a dynamic runtime. Configuration is authored as KCL functions that deterministically emit Kubernetes resources, while correctness is asserted through executable tests that observe reconciliation outcomes rather than driving provisioning imperatively. The goal is not to simulate Kubernetes, but to treat it as a system under observation whose behavior can be reasoned about through stable, inspectable artifacts.

The examples below make this split explicit. KCL is used as a JSON-like, declarative format that deterministically emits Kubernetes resources and nothing else. Expressive logic and validation live in Python, backed by fully typed APIs that observe reconciliation outcomes rather than orchestrating them. This separation keeps intent readable, behavior testable, and authority out of scripts.

import schemas.kcl.fluxcd_helm_controller_kcl.models.v2.helm_toolkit_fluxcd_io_v2_helm_release as fluxcd_release

fluxcd_release.HelmRelease {

metadata.name = "traefik"

metadata.namespace = "traefik"

spec = {

interval = "10m"

chart = {

spec = {

chart = "traefik"

version = "21.2.0"

sourceRef = {

kind = "HelmRepository"

name = "traefik"

namespace = "traefik"

}

}

}

install = {

createNamespace = True

}

}

}

And its corresponding test.

@make_kcl_named_test(["crossplane_release.k"], lambda kf: "helm_releases" in kf.path.parts)

def e2e_frp_kuttl(crossplane_release: KFile) -> None:

# Run flux sync

subprocess.run(["flux", "run"], stdout=subprocess.DEVNULL, stderr=subprocess.DEVNULL)

# Parse HelmRelease from KCL output

result = Exec(crossplane_release.path).json_result

release = HelmRelease.model_validate(json.loads(result))

metadata = release.metadata

# Check required metadata fields

if not metadata or not metadata.namespace or not metadata.name:

raise ValueError("HelmRelease.metadata.namespace and name are required")

namespace_name = metadata.namespace

release_name = metadata.name

# Ensure namespace exists

try:

Namespace.get(name=namespace_name)

print(f"Namespace '{namespace_name}' already exists.")

except ResourceNotFound:

ns = Namespace.builder().metadata(lambda m: m.name(namespace_name)).build().create()

for event, _ in ns.watch():

if event == "ADDED":

print(f"Namespace '{namespace_name}' created.")

break

# Ensure HelmRelease exists

try:

HelmRelease.get(name=release_name, namespace=namespace_name)

print(f"HelmRelease '{release_name}' already exists.")

except ResourceNotFound:

for event, _ in release.create().watch(namespace=namespace_name):

if event == "ADDED":

print(f"HelmRelease '{release_name}' created.")

break

Conclusion

The tools we use to manage infrastructure are not neutral. They encode assumptions about who is allowed to act, how change is coordinated, and where authority lives. Over time, those assumptions shape teams as much as they shape systems.

Terraform centralizes coordination. Pulumi maximizes expressive power. CDK8s constrains execution while preserving authoring flexibility. YAML and bash trade guarantees for immediacy. None of these approaches are wrong — but each makes a different trade between power, legibility, and control.

The system described here explores a different point in that design space. By treating infrastructure coordination as a control-plane problem, and by insisting on static, inspectable interfaces between roles, it becomes possible to automate aggressively without obscuring intent.

Infrastructure systems shape how teams think, collaborate, and make changes under pressure. By designing for legibility as carefully as we design for power, we can build control planes that more than just automate infrastructure — they make coordination itself easier.

That tradeoff — less power, more understanding — is the one I’m most interested in exploring.